In my last couple posts on TCP congestion control, I discussed strategies that TCP senders can use to handle congestion and figure out the optimal rate at which to send packets.

In this post, I’m going to change it up and talk about strategies that routers can use to prevent congestion. Specifically, I’m going to focusing on an algorithm called Random Early Detection (RED).

As usual, I put together a Jupyter notebook documenting my results and explanations.

Recap: Congestion Control

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, congestion happens in computer networks when senders on a link send more packets to the link than it can handle. As senders on a particular link send more packets to the link, if the link cannot accomodate the quantity of packets being sent, the router connected to that link will begin queueuing up those packets. If the queue on that router fills up, subsequent packets arriving at the router will get dropped.

When this situation occurs, TCP senders need to reduce the rate at which they send packets. There are two indicators that TCP senders have that congestion is happening:

- Packet drops

- Increased round trip times

While senders could theoretically use both of these signals to control the rate at which they send packets, in reality, many TCP implementations only use packet loss.

Why might this be an issue?

If TCP senders only react to packet loss, that means that if they are sending too many packets, they only find out once the queues at the routers fill up. In cases where there is a sizable queue, that queue will delay the time it takes for the sender to realize that congestion is happening. In the case of CUBIC, the default congestion control algorithm on Linux, the sender will ramp up its window will grow its window really fast, fill up the queue buffer, see a bunch of packet loss, and then drop its window size very quickly.

In this world, it becomes very hard for CUBIC to fully achieve its potential, because it gets signal about how much congestion is happening too late. It makes the link kinda like the hot water knob in the shower–the feedback happens after you’ve moved the knob, and you don’t realize if you’ve made it too hot until later.

More on the queues

It sounds like from this that the queues are masking congestion issues, and possibly even making the problems these links experience worse. So why not just make queue smaller?

I think to understand this requires an understanding of why these queues exist in the first place. The reason we want routers to have queues is because traffic isn’t consistent–it’s possible that in one minute there’s a sudden burst of traffic because a bunch people decided to visit a website at exactly the same time. If links dropped packets immediately after the link capacity is full, they would have no resilience to bursts of traffic. Queues can serve as smoothing functions that can absorb bursts of traffic and hold them while the link is being emptied.

Throwing away the queues or making them smaller makes them less resilient to bursts of traffic.

Can you manage queues differently?

Alright, we’ve established that queues are important, but that they can mask congestion problems.

It turns out that changing the way the queue is managed can preserve the benefits of having queues, and also solve the congestion masking problem. This general approach of changing how a queue handles filling up is called Active Queue Management (AQM).

When I talk about how queues are “managed”, I’m specifically referring to how they handle being too full. The traditional, intuitive approach to handling this is called droptail. The way droptail queues work is that they fill up until they hit capacity. Once they hit capacity, all subsequent attempts to add packets to the queue fail.

However, queues don’t have to wait until they are full to begin dropping packets.

Introducing RED

Random Early Detection (RED) is a queueing discipline that drops packets from the queue probabilistically, where that probability is proportional to how full the queue is. The more full the queue is, the higher the probability of a drop is.

Here we see that as the queue is emptier, packets don’t get dropped, but as the queue gets more full, it begins to drop packets with more frequency.

Drop healthy packets?

It’s a little counter-intuitive that dropping perfectly healthy packets arbitrarily would lead to better performance. The intuition though, is that dropping packets earlier provides an indication to TCP senders that they should reduce their congestion windows. This is a much better situation than letting the senders fill the queue entirely, experience a whole series of drops, and then have to dial down their congestion windows a lot.

Results

In every scenario that I ran, RED performed better than droptail. While the differences were more subtle on low BDP networks, there was a pretty dramatic improvement on high BDP networks.

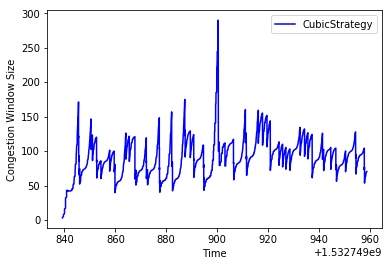

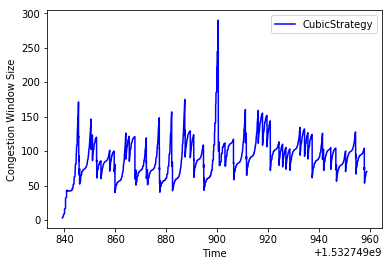

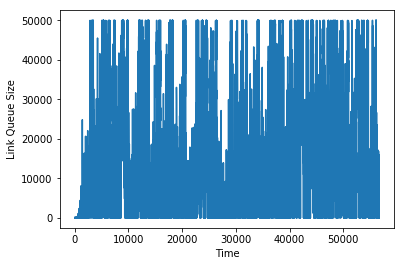

CUBIC running on a high BDP network with droptail

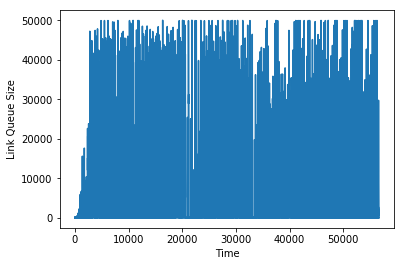

CUBIC running on a high BDP network with RED

The intition for why RED performs so much better here is that in the droptail case, CUBIC is constantly alternating between filling up the queue, and then dramatically dropping the congestion window when a bunch of drops happen, while in RED, drops happen earlier, resulting in fewer consecutive window size reductions.

This is apparent in graphs of the link queue sizes in each of these scenarios:

Link queue size using droptail

Link queue size using RED

Some Implementation Details

I worked with a fellow Recurser, Venkatesh Srinivas on actually writing an implementation of RED in a network simulator I’ve been using for congestion control experiments.

The RED Paper has a full section on the recommended implementation. One of the most important takeaways from this is that when computing the probability of dropping a packet, the paper recommends using a weighted average of the queue size, rather than the queue size in any given moment.

Using a weighted average of the queue size makes the algorithm more resilient to a sudden burst of traffic. If a new flow randomly pops onto the network throws a bunch of packets onto the queue temporarily, that doesn’t necessarily mean that congestion is happening. We only want to increase the probability of a drop if a standing queue is building–meaning that the queue is high for a period of time.

The way you compute the weighted average is as follows:

is some parameter to the RED queue, and is a measure of how much you want to weigh recent measurements of the queue size relative to older measurements. This gives the the property that older measurements of the queue size decay exponentially. We do this update every time we enqueue a new packet to figure out whether it should be dropped or not.

A Bug

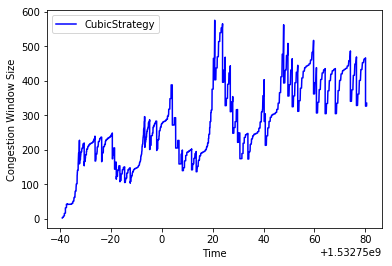

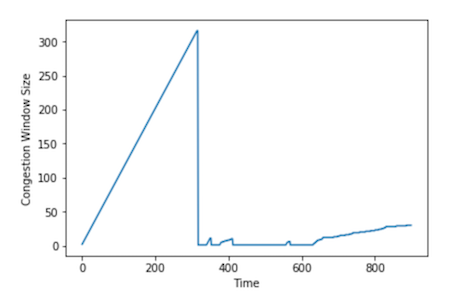

Alright, that all seems fine–but when we actually wrote up our implementation, we started noticing some odd behavior. Notably, on some experiments, the congestion window would just collapse to nothing and never recover. We’d see graphs like this for the congestion window:

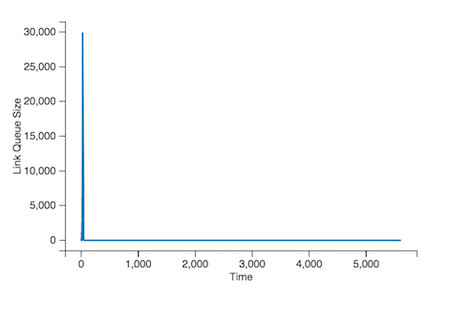

And the link queue size graph would look like:

It took us a while to figure out what was going on here, but we ultimately figured out that there’s a negative spiral that happens:

RED begins dropping packets probabilistically because a queue starts filling up. The TCP senders begin dropping their windows, resulting in fewer packets being sent through the link. Since the window size is now small, even though the link queue is empty, the weighted average is still very high. This results in packets continuing to be dropped, resulting in TCP senders dropping their senders. Since fewer packets are arriving at the link now, there are fewer opportunities for the weighted average of the queue size to be updated.

A Solution!

The fundamental problem here is that if packets aren’t arriving at the queue, and the queue is empty, there is nothing that happens to the weighted average.

The solution to this is to behave differently when packets arrive at an empty queue. Rather

than simply decaying the existing average by wq, instead, decay it by the amount of time

that the queue has been empty.

Here, average_transmission_time is the typical amount of time between packet enqueues. This

way, if packets don’t arrive at the queue for a little while, that gets taken into account

in the weighted average calculation.

This problem and solution was laid out in the paper, but it was cool to have discovered this on our own.

Next up

While RED in our examples performs much better than droptail, it does have some weaknesses–for instance, RED requires some tuning to work effectively. It has a handful of parameters, including the term that we discussed earlier, and there isn’t a clear science for figuring out the right values for these parameters. There are other AQM approaches that are more commonly used today, like CoDel.

In the next couple posts, I’m going to return to solving congestion at the sender level and discuss some of the work that I’ve been doing around using reinforcement learning to help senders find the right congestion window.

Thanks for reading!

Big thanks to Venkatesh Srinivas for the help implementing this, and for the introduction to queueing theory!