In April of this year, Jeff Dean from Google released a paper titled “The Case for Learned Index Structures”, where he detailed his experiments replacing database indexes with neural networks. In the paper, he finds that the neural network-based “learned indexes” actually do perform better than some of the currently used indexing methods.

The fact that this work is even possible is pretty incredible, and has some really interesting implications. On this surface level, neural network replacements for existing algorithms means that in the future, we’re likely to see better performance from commonly used systems like databases. The deeper, more interesting realization, however, is the possibility of many specialized algorithms and data structures being replaced by more generalized “learned” algorithms and data structures.

This summer, I am attending the Recurse Center, and will be spending time experimenting with this approach of replacing specialized algorithms in different software systems with “learned” algorithms.

For starters, let’s unpack what’s going on in Jeff Dean’s paper, with a focus on B-Tree indexes, a particular type of database index.

B-Tree Indexes and Databases

The first step in understanding this paper is reviewing what exact problem a B-Tree solves in a database. Let’s take this database of names as an example:

| Id | Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | San Francisco |

| 2 | Bob | New York |

| 3 | Chalie | Boston |

| … |

It’s important to note that data in a database is stored in “pages” (it’s not super important for the purposes of this paper to understand exactly what they are), and that the first step of retrieving data from the database is finding the page that that particular piece of data is stored on.

Let’s say given an ID, like 2, we want to be able to retrieve the data associated with that ID, in this case “Bob, New York”. Without any sort to the data at all,

in order to retrieve that data, you’d have to do an O(n) full scan of the database. This problem is solved with what are called indexes. An index is a data structure

that allows faster access to particular data in the database.

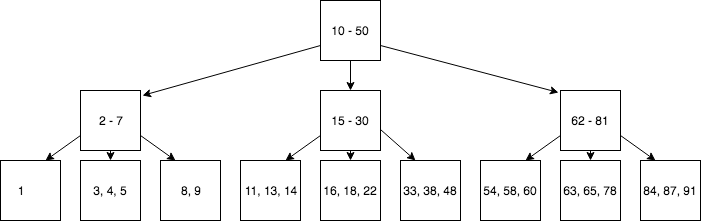

A common data structure that is used to index databases is the B-Tree. A B-Tree is a tree data structure in which each of the nodes corresponds to some range of keys. B-Trees are configured to have a fixed number of children per node, and each child contains a subrange of the node’s range of keys.

An example tree might look something like:

Inserting a value into a B-Tree is done by traversing the tree to find the leaf for the value, and adding the value to that leaf. If the leaf is “full”, a new level will be added to the tree.

B-Trees are widely used because they are easier to keep balanced than other tree structures, at the cost of potentially being more wasteful with space. Using a balanced tree is the key to maintaining the worst-case performance of O(logn) lookup times.

B-Trees are classifiers

They key insight in Dean’s paper is that the problem of finding the page on disk with the value you are looking for seems a lot like a classification problem in machine learning, and that B-Trees seem an awful lot like a classifier. They take a potential key as an input, and output one of many pages that the value you are looking for is on.

What is the point of looking at things this way? Well, we know that the runtime of looking up values in a B-Tree is O(logn), where n is the full size of the data set. In other classifiers, for instance, neural networks, the runtime of the classification of a value (not the training), doesn’t actually scale with the size of the data set. Rather, it scales with the number of “neurons” that are used in the network, which is a constant value.

Switching out B-Trees for a “learned” data structure like a neural network then has a potential for vastly increasing the speed of looking up values in a database.

Learned Indexes

Dean calls these machine learning-based indexes “learned indexes”. The general idea behind these is that instead of building a B-Tree to be used to figure out where on disk to look for values, training a machine learning model, using the database keys as data points, and location on disk as labels.

As I mentioned before, the advantage of doing this is speed–classification with standard machine learning algorithms does not scale with the size of the data set. The downside, however, with any kind of machine learning approach like this is that the algorithm may not always spit out the right answer.

In this particular example, because the data on disk is sorted already, errors can be corrected fairly easily by doing a simple local search around the prediction given by the machine learning algorithm.

Model Selection & Performance

Ok, so theoretically, it seems like replacing B-Trees with some machine learning model should be possible. The next challenge, then is figuring out exactly what model to use. This involves weighing the tradeoffs of particular methods and understanding the performance of various models. Important factors to understand here are that if the model returns an inaccurate result, cost will be incurred dong a search to find the actual value, and that a model that is slower to execute but returns a more accurate result might actually be faster because of the lower local search cost.

What Dean and the other researchers ended up choosing was a “Recursive Model Index”, in which many models are trained on subsets of the full data set. A higher level model is run first, and selects one or more of the models trained on a subset of the overall data. The insight here is that narrowing the result set from 10M records to 100 records is very hard to do precisely, but then narrowing fewer orders of magnitude, from 10M to 10k or from 10k to 100 records is much easier to get precise results with. An advantage of using this “staged” model approach is that a mixture of models can be used–for instance, neural networks for the top level and linear models for the models trained on the subsets of the data.

So far, I’ve been talking about big O performance, but in order for this approach to work in actual production system, the actual time in seconds needs to be faster. Dean and the other researchers did a bunch of experiments on a few different data sets with different configurations of machine learning algorithms and B-Tree page sizes, and found that the learned indexes performed 1.5-3x faster than the B-Trees and use less space. The paper has the specific numeric results.

Another key point that Dean makes in this paper is that specialized machine learning hardware is improving, and as time goes forward, approaches like this will become more and more feasible.

What I haven’t talked about here

There is a lot of other material in that paper that I haven’t covered here. Some of the issues include:

- Replacing other common database indexes, such as Bloom Filters and Hashmaps, with learned structures

- Handling string keys (the examples I used were integers)

Conclusion & Future Work

The implications of this work are really exciting. Advances in hardware for machine learning are going to make including machine learning approaches in software systems much more feasible. A lot of the algorithms used in software systems, such as B-Trees, are designed to not make any assumptions about the distribution of the data that the algorithm is operating on. Being able to use neural networks and other machine learning tools in these software systems means that we can start to take advantage of patterns in the data that the algorithms operate on to improve the speed of these systems.

Where else could this approach be useful? At the end of the NIPS presentation on this paper, Dean posits that ML could be used in software systems where blunt heuristics can be used, including in networking, operating systems, and compilers.

This summer, I’ll be attempting to apply this technique to software systems, and will be starting with TCP congestion control. Stay tuned!